As part of a Valley Profile series, MEGHAN HAWKES explores our local history by seeking out stories of life and death in the Thames Valley

PART TWO

At Kōpū, Commissioner James Mackay began investigating the truth of reports that Paora had been murdered by white men.

An accusation had also been made that Europeans had broken into and plundered the house of Haimona Kewha when he went to bury Paora.

Five flax mill workers were apprehended on suspicion of stealing a gun, pot, camp oven, blanket, shirt, trousers, powder, shot and tin dish.

Mackay then questioned Tukukino, who said he had discovered Paora lying dead. Blood flowed from his right eyebrow, which appeared to have been cut with a knife or a kick from a boot. There were five stab wounds on the right side, starting under the armpit, and extending to the calf of the leg.

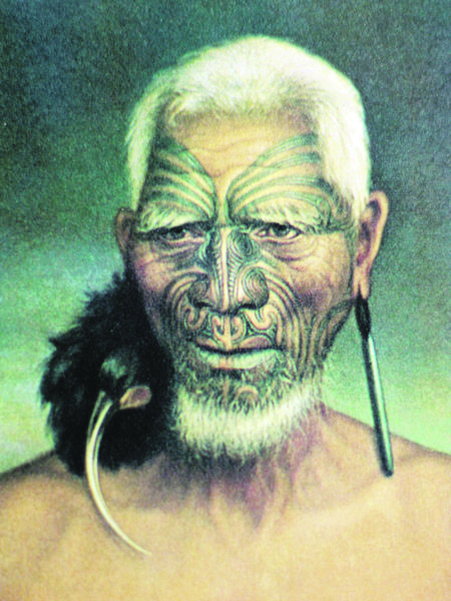

Ngāti Tamatera were adamant Paora was killed by European flax cutters, but Ngāti Maru suspected it was the work of Ngāti Tamatera, as they had threatened to kill Paora for practicing mākutu (witchcraft).

During several stormy discussions, Mackay asked to be allowed to dig up body so that he might see the wounds. Ngāti Tamatera objected very strongly, but Ngāti Maru showed support.

Undaunted, Mackay, along with Māori police and others, proceeded secretly up the river to where Paora was buried. They dug up the body and found no wounds or any marks of violence on it. On their return, the items stolen from Haimona’s house were recovered from the river. The party then returned to Kauaeranga, undiscovered.

The next day the five prisoners were convicted of theft, and sentenced to three months’ imprisonment, with hard labour.

Mackay then addressed Ngāti Tamatera and Ngāti Maru. He had not believed Paora was murdered from the start – it was improbable that any person would lie quiet to be stabbed six times on one side. He also found the reluctance of Ngāti Tamatera to co-operate suspicious. He cautioned them against ever repeating such accusations, which appeared to have been made to cause ill feeling between Māori and Europeans.

Riwai Kiore made a poignant plea – “I do not want any fresh faces here. Keep away all you Europeans. I like my old friends and those who can speak the Māori language. I do not want any flax-cutters here. I do not want any gold diggers here. If they come, disputes will arise. All this has come from the Europeans coming here to dress the flax. Let them remain at Auckland.”

Despite the words of Hohepa Paraone – “Mr Mackay has done quite right. He has found out the truth. He has removed the evil from Hauraki,” misfortune continued to plague the Kōpū Flax mill. Work resumed but it was questionable whether sufficient quantities of flax could be procured unless new arrangements were made with Māori.

A few days after the alleged murder, a child named Ellen Clark drowned in the Kōpū flax mill’s well. No inquest was held and no trace of Ellen is left.

By October, 1866, just 10 months after opening, the Kōpū Flax mill was up for sale, its collapse a consequence of unwise expenditure and the long shadow of the negative effects of colonisation.