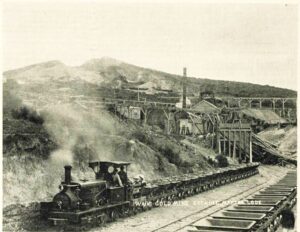

As part of a Valley Profile series, MEGHAN HAWKES explores our local history by seeking out stories of life and death in the Thames Valley

Something was coming down the shaft near where William Lawrence was working in the Waihī mine between No 5 and 6 levels.

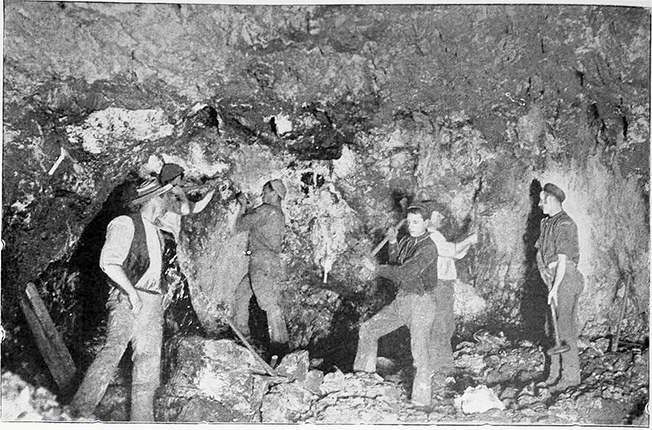

It was around 2:25 on a Monday afternoon in April, 1903, and William was in a stope, an area where rocks were hauled out and excavations made.

Somewhere above him, John Hollis had been giving John Bennington a hand with taking a mine cart of timber along fixed tracks from No 2 shaft.

They had to cross over Elliott’s Pass and John Hollis, in front, called out to John Bennington to look out for the iron bar guard.

“All right,” replied Bennington as Hollis went on ahead with his truck.

But John Bennington never made it over the pass. William Lawrence, investigating the noise he had heard, was horrified to discover John head down on a heap of waste rock. John had fallen 125 feet. He was lifted out and his mates went for help.

Dr Guinness found John badly injured and unconscious. He had him removed to Nurse Arnaboldi’s private hospital*. About 8:30 that night Dr Slater joined Dr Guinness at the hospital and together they examined John.

His injuries were consistent with a great fall.

He died shortly after the examination. At the inquest, which was held after the jury had been taken to the scene of the accident, John Hollis said the guard iron was 10ft from the mouth of the shaft and a light was burning there. John Bennington had been over the pass several times before. Hollis considered that the bar and light were sufficient protection and he didn’t think better provision could be made for safety.

Dr Guinness said head injuries were the cause of death and the jury’s verdict was that John Bennington had met his death by accidentally falling down a shaft in the Waihī mine. There was no blame whatever attachable to anyone and every precaution appeared to have been taken.

Thirty seven-year-old John was married with two children and his wife Ellen was pregnant with their third. For several nights John had been sitting up with his wife tending to one of their children who was very ill.

It was thought that he had been suffering from exhaustion when he fell down the pass.

John was a steady, reliable worker and well liked by his work mates and the community, many who attended his large funeral at Waihī cemetery.

In May, the Waihī Miners’ Union sent Ellen the sum of 50 pounds. Compensation of three years’ full wages was also paid to Ellen by the New Zealand Accident Insurance Company, a manager commenting: “We have never before had such a cyclone of accidents as during the past few months, not only at Waihī, but at all mines, small and large, all over the fields”.

In September, Ellen Bennington gave birth to a daughter.

Three years later John and Ellen’s son, Leslie, aged 5, was killed when he was run over by a spring cart at Mt Roskill, where Ellen had moved after re-marrying.

*Nurse Dora Arnaboldi, who exposed patient negligence at Auckland hospital and was named New Zealander of the year in 1891, opened her private cottage hospital at Waihī in 1895.