As part of a Valley Profile series, MEGHAN HAWKES explores our local history by seeking out stories of life and death in the Thames Valley

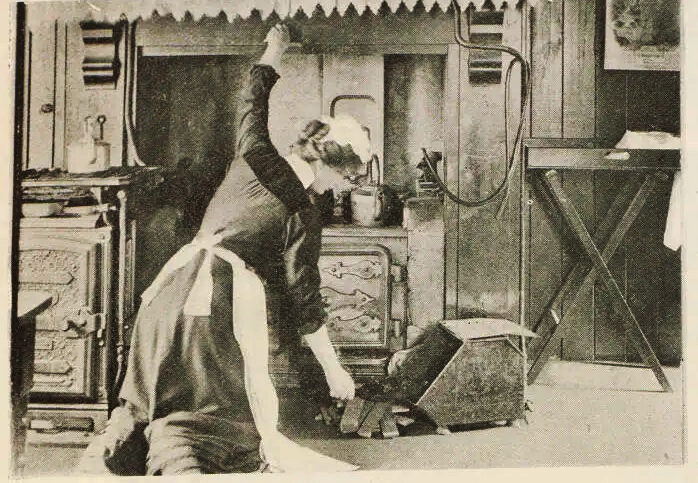

Seventeen year old Mabel Kennedy was cooking lunch over an open fire in the kitchen of her employers, the Moore family, at Mill Road, Paeroa. The range, which was usually used, had been taken outside to cook on during the hot summer of 1914.

It was now the end of March and cooler in the kitchen. Mrs Moore and the children had gone for a walk and Mr Moore was lying down. A boy named James Smith, 15, was also on the premises.

Suddenly Mabel’s apron caught fire and she and James hastily tried to put it out but couldn’t. Mabel rushed outside and across a paddock before jumping into a ditch full of water.

This extinguished the flames but Mabel was badly injured. Mr Moore was roused from his rest by the commotion. He gave what help he could to Mabel and called for first aid remedies to be collected from the Gold Extraction Company’s works. Dr Smith was sent for, and on arrival dressed the wounds. He ordered Mabel’s removal to Thames Hospital, where she was taken, in a very critical condition, by the afternoon train.

The Kennedys, of Corbett St, Paeroa, had already been dealt one dreadful blow with the death of a son just three months earlier. William Kennedy, 27, had drowned while swimming in a storage dam at the Waihī Paeroa Gold Extraction Company after work.

Six days after her accident, local newspapers were pleased to report that Mabel was progressing favourably and there was every hope that she would recover. But within weeks, despite Thames Hospital’s Dr Foote and his staff doing everything possible for her, she gradually sank and died in May.

Her parent’s heartfelt thanks for the attention and kindness given to Mabel were published in a general notice in the Thames Star.

The speed of the fire had been fatally fuelled by flannelette, a fabric used in undergarments and nightwear. Flannelette was a plain-weave cotton with a raised fluffy surface which, if a spark landed on it, transformed into a sheet of rapidly moving flame. Its dangers were well known and it was the cause of many deaths.

Coroners and inquest jury’s were vocal in their opinion of flannelette – one jury in 1910 asked that the Public Health Minister condemn its use in the cause of humanity.

Many lives had been sacrificed through its use and it should be banished from every household. In 1913 a coroner stated that in view of the large number of cases where the fabric was responsible for fatal burns, it should be made a crime to wear flannelette.

As a general servant Mabel’s days were busy with cooking, cleaning, and washing, dealing with trades people and receiving visitors. She probably gave a hand with the children, the vegetable garden and clothes mending. A large part of her work involved the use of fire.

Mabel was buried with her brother at Paeroa’s Pukerimu cemetery.