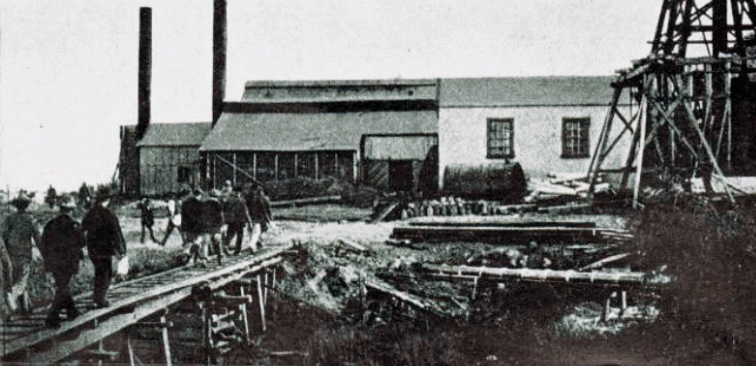

As part of a Valley Profile series, MEGHAN HAWKES explores our local history by seeking out stories of life and death in the Thames Valley.

At ten to eight on a May morning in 1903 Richard Lindsay and Jeremiah ‘John’ Landrigan came on shift at the Waihī mine.

The men were sinking a winze – a small shaft between different mine levels – from No. 6 to No. 7 level. The night shift, just prior to knocking off, had blasted the rock and dirt with gelignite, which made a terrific black smoke. In order to allow the smoke to clear Richard and John waited a little time at the top of the winze.

After the smoke lifted John elected to fill the buckets with the loosened debri while Richard remained on top to work the windlass. He lowered John down in the bucket.

After four buckets had been hauled up, the fifth was within about two feet of the top of the winze when the wire rope suddenly broke. Richard immediately called down a warning to John but the bucketful of dirt shot to the bottom, striking him. Richard ran along the level to get help and then hastily returned, descending the ladder to the bottom of the winze. Preparations were made to bring John to the top of the winze, and then he was transferred to the surface, where Dr Guinness, who had been summoned, was waiting. On examination the doctor found that life had been extinct for some minutes.

Thirty two year old John, an Australian, had been in Waihī three or four years. Two years previously he had married and he and his wife, Amelia, had a son, just over a year old. John had been a miner for over 14 years and was well known and liked in Waihī.

At the inquest Richard Lindsay said John could not have escaped the falling bucket unless he had seen it coming. They had used the rope for about a week. He noticed no breakages in the rope before it gave way. The shift boss, William Jones, passed through about ten minutes before the accident and remarked that the rope was getting short and they must get another one. Richard and John had examined the rope before commencing work. They thought it was all right.

James Gilmour, mine manager, said if a man wanted a new rope it would be supplied within half an hour or so. He was of the opinion the rope had been cut by a sharp piece of quartz. William Jones said the rope had been put on some time the previous week. It was not new and had been used in another winze. He considered the rope to have been sound and safe.

The coroner said the rope was chewed from use, which possibly was due to a piece of quartz cutting it. A measure of blame, he thought, was attachable to the shift boss and to the workmen themselves. To examine the rope properly it should have been taken off altogether. The verdict was that John met his death by the breaking of a wire rope which had been worn at the handle of the bucket until too weak to carry the strain.

John was buried at Waihī cemetery. Amongst those at the funeral were representatives from the Waihī Miners’ Union and the Oddfellows’ Lodge, John being a member of both. A month after John’s death the Waihī Miners’ Union sent 50 pounds to his widow who had waited in vain for her husband to return from his last shift.