As part of a Valley Profile series, MEGHAN HAWKES explores our local history by seeking out stories of life and death in the Thames Valley.

When a dog fell on him it was the beginning of the end for Thomas Bennett Hicks.

The Thames mine manager was climbing down a shaft in the City of London mine when at about 150ft the dog struck him on the chest with such force that one of his lungs was permanently injured.

It was 1878 and Thomas, from Cornwall, was second to none on the Thames Goldfield as a mine manager. He had initially worked in tin mines before travelling to North America to try the copper mines.

In 1854 he was lured to Australia by gold discoveries there. He held responsible positions in several mining centres but it was at Daylesford in 1865 that he was first appointed mine manager.

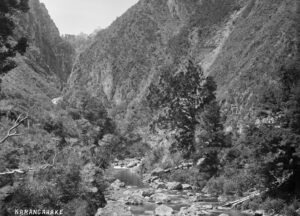

Here he displayed the great energy which would characterise his career. After a return to England he migrated to New Zealand’s West Coast goldfields finding his way to Thames with his wife Barbara, known as Annie, in 1868. Here he helped sink the first framed-set shaft on the field at the Kuranui mine.

Soon afterwards he was appointed manager of the Golden City and Grand Trunk mines at Punga Flat, for several years confidentially advising Warwick Weston, who was involved with several mining companies and commercial interests.

The dynamic Thomas then took charge of the Deep Lead mine in the Shotover Creek, and afterwards the Inverness mine. Next was the City of London, which he successfully worked for several years but now weakened by the blow from the dog he decided to leave mining alone for a spell.

He bought a farm at Pokeno. Before he left he was presented with a testimonial from his Thames friends.

In July, 1881, Thomas lost his wife Annie who died aged 43. The couple had been childless. In December, he had a farm clearing sale and it was leased out.

He had been persuaded to take over the management of the Caledonian mine at Thames where he returned. By 1888, with his health failing, he went overseas for twelve months.

He returned to Thames in much the same condition, the trip having failed to do him much good.

Despite this in early 1892 he took over the management of the May Queen mine but by late 1893 even with his strong constitution, he was compelled to resign and for two months was mostly confined to his bed.

Thomas was a man of great determination and force of character but in the end he could not fight off this last adversary. He died around twenty to five on a late January morning in 1894, aged 61.

Thomas was known for his kind-heartedness and modesty, his purse and helping hand gave many a fresh start in life.

His death in every way was a loss to the district. A few weeks before his death, Thomas had presented the Thames School of Mines with his private collection of ores and minerals, together with a handsome showcase made of mottled kauri to exhibit them in.

The collection included specimens of silver ores from Broken Hill, horse-flesh ore, grey glance, bell-metal and other ores of copper from South Australia.

There were fine gold specimens from the old City of London, Caledonian, and other Thames mines, all of which were of considerable historic value.

In making the presentation, Thomas said all through his career he felt he needed technical training, and he strongly urged all young miners to make the most of their opportunities and attend the school.

Only those who possessed sound technical training would succeed as the mine managers and battery managers of the future.

Thomas was buried at Shortland Cemetery, alongside Annie.