As part of a Valley Profile series, MEGHAN HAWKES explores our local history by seeking out stories of life and death in the Thames Valley

October 1870 had been challenging for the Collett family, owners of the Tararu store. Henry Collett had recently filed for bankruptcy, a casualty of the struggle for survival on a goldfield then in its third year. For Mrs Collett the sight of a dray carrying Thames’ famed gold quartz from the Golden Crown mine to the Tararu battery must have been bitter sweet.

To avoid a bad piece of road, drays had been making a detour behind the Royal Hotel. A surprised Mrs Collett noticed that the driver was lying back in the cart. Her bemusement turned to horror when she saw her daughter lying in the cart track directly after the dray had passed.

Helena Collett was 15 months old and had been playing near the peach grove opposite Mr Graham’s cottage. When her frantic mother picked her up the child breathed with difficultly and gave a faint cry. Bystanders ran to the dray and found the driver, Thomas Crowe, so profoundly asleep that it was almost impossible to wake him. Dr Hunter at first thought Helena had received no serious injury but she died during the course of the evening. An inquest was held at the Tararu Hotel. Thomas Crowe was proved to be drunk and asleep at the time the horses were making their way to the Tararu battery. After a lengthy sitting, a verdict of manslaughter was returned and he was committed to stand trial at Auckland’s Supreme Court. At the trial in December, Thomas Crowe, aged 32, was described as a labourer, single, Church of England and a man who could read and write. He pleaded not guilty. The prosecution said Crowe heedlessly allowed his horses to go their own way, and that his negligence resulted in the death.

Helena’s mother was very distraught while giving evidence. Thomas was found not guilty. His Honour discharged the prisoner, and irately remarked on the reckless manner in which drays were driven.

But things were not what they seemed. A good character was given of Thomas Crowe. He was not a man with a drinking problem and there was no evidence that he was drinking that day. It was suggested that the heat of the sun, acting upon the brain affected by drink, threw the accused into an almost impenetrable sleep and the accident was misadventure.

Men in mines worked 12 hour shifts at this time despite the call for shorter hours after an horrific accident killed the head engineer at the Golden Crown mine a year earlier. At that inquest, a rider was added that an eight hour shift be introduced as a man was likely to get worn out, drowsy and accident prone by the long 12 hour shifts.

On the day of Helena’s death Thomas Crowe had worked a gruelling 18 hours. Helena is buried at Shortland cemetery, a tragically indirect victim of the terrible working conditions surrounding the pursuit of gold.

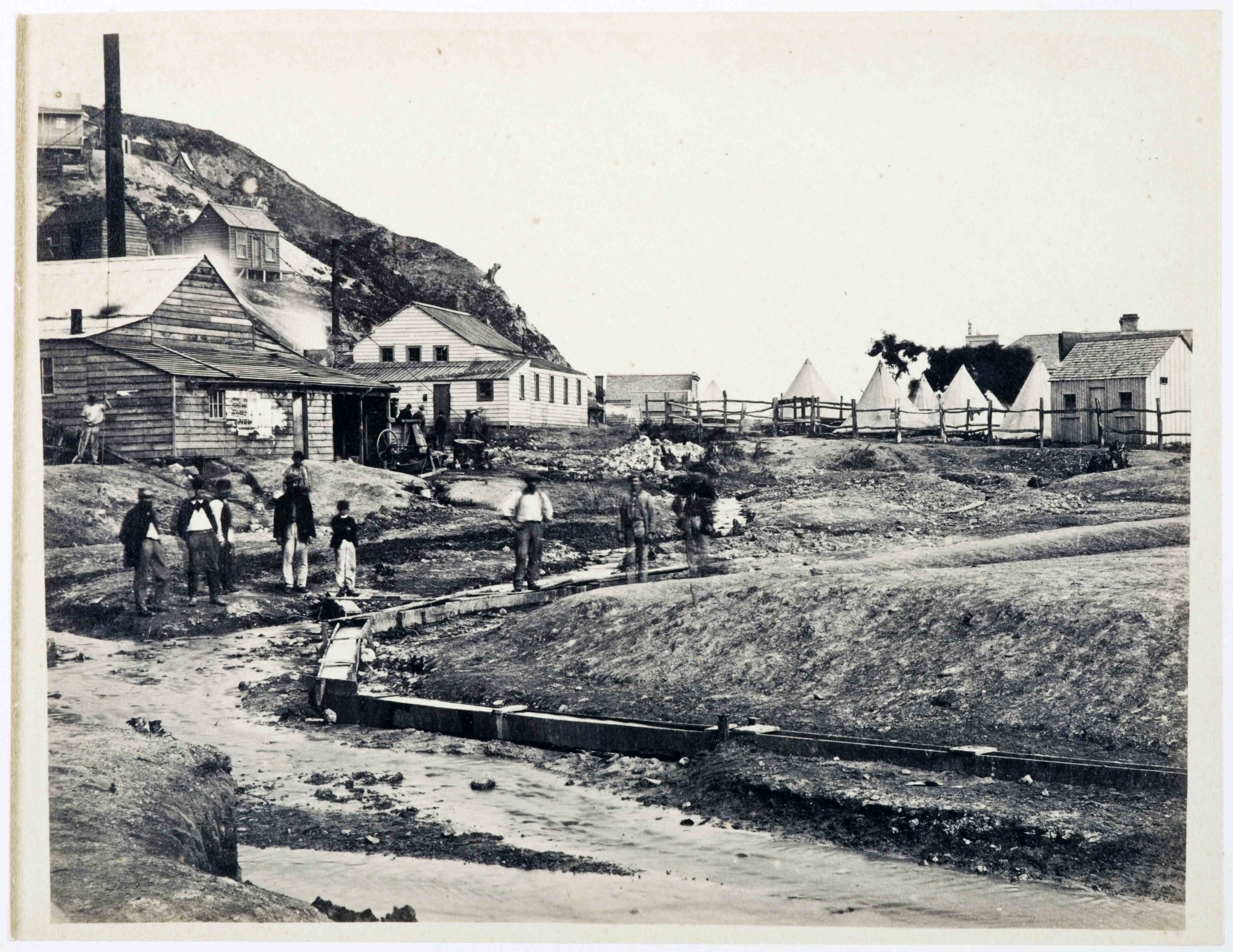

PHOTO: The dark side of gold – the Golden Crown battery, Tararu. Photo: SUPPLIED